India Poised to Emerge as Global Sustainability Leader: Primus Partners MD

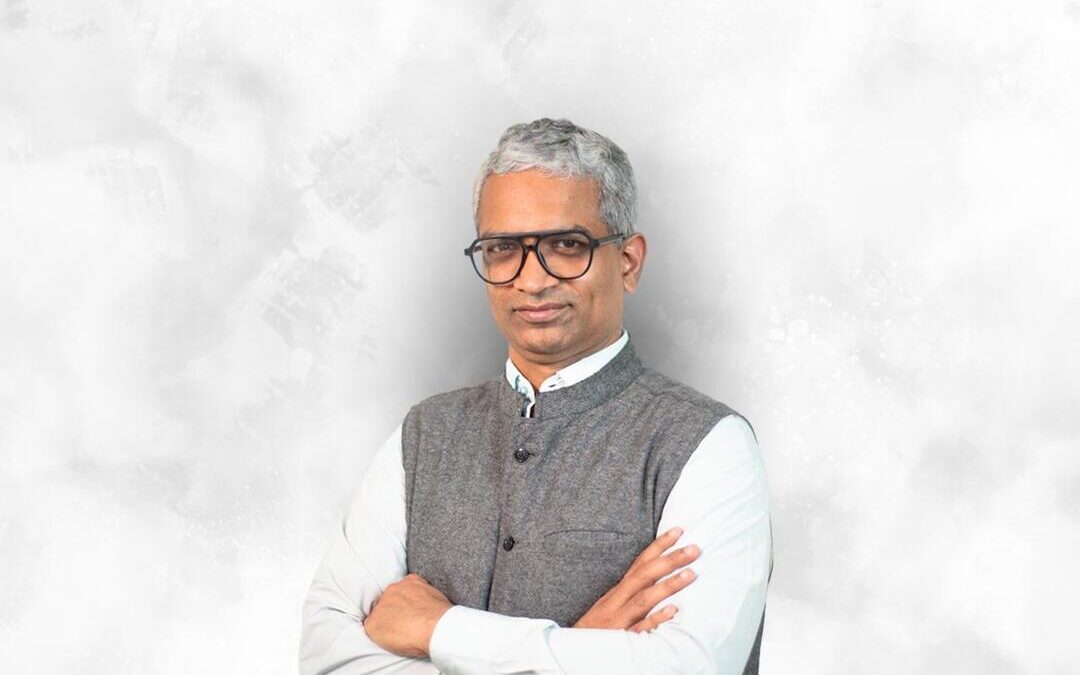

Primus Partners MD M. Ramakrishnan says India’s choices in the next five years will define its global sustainability leadership.

Primus Partners Managing Director M. Ramakrishnan leads the firm’s Agriculture and Sustainability Practice and has spent over two decades advising businesses, governments and start-ups.

With over seven years of experience in agritech and sustainability, he has helped companies establish net-zero goals, enhance compliance, and develop resilient business models. His expertise spans enhancing farmer income, improving access to credit, promoting soil health, reducing chemical and water use and leveraging AI to curb food loss.

In this wide-ranging interview with Nirmal Menon, Ramakrishnan shares his perspective on India’s evolving ESG landscape, from disclosure norms and board governance to net-zero pathways, carbon markets, just transition and the role of finance in positioning India as a global sustainability leader.

NM: How do you see India’s ESG disclosure journey evolving under BRSR and SEBI guidelines compared with frameworks like CSRD and ISSB?

MR: India’s ESG disclosure landscape is at a transformative stage. With SEBI introducing the Business Responsibility and Sustainability Reporting (BRSR) Core for the top 1,000 listed companies, ESG has moved from being a voluntary add-on to a mainstream requirement. What sets BRSR apart is its push for standardisation and assurance. For the first time, Indian companies are being asked to share verifiable, comparable ESG data that investors can actually use to make decisions.

Compared to global frameworks, the approach is different. The EU’s CSRD requires “double materiality,” i.e., companies must disclose how sustainability issues affect them and how their operations affect society and the environment. ISSB, meanwhile, is focused on global consistency, especially in climate-related disclosures.

India’s BRSR is more flexible and principles-based, acknowledging the diversity of the Indian corporate landscape. Over time, though, India has signalled that it will align with ISSB to stay connected with global capital markets.

This creates both opportunities and challenges. Companies with international investors will need to meet multiple frameworks simultaneously. This means building stronger data systems, governance structures and reporting processes. The challenges are real: smaller firms lack capacity, assurance expertise is still catching up, and weak enforcement risks greenwashing.

What we are seeing is a move towards convergence. Indian companies, particularly those with global investors, will have to report in formats that align with CSRD and ISSB while also meeting SEBI’s requirements. This dual demand will push companies to improve their reporting systems, governance structures, and internal data systems.

Looking ahead, the direction is clear. SEBI will gradually expand BRSR beyond the top 1,000, make assurance more rigorous, and bring India closer to ISSB alignment. For Indian corporates, this journey is not just about compliance – it is about building credibility in global ESG markets and positioning themselves to access the growing pool of sustainability-linked capital.

NM: How effectively are Indian boards incorporating ESG into their corporate strategy compared to global peers?

MR: Indian boards are gradually embedding ESG into strategy, but the gap with peers in Europe and North America remains. In global markets, ESG is no longer treated as a “nice-to-have” but is firmly tied to financial performance, risk management, and even executive remuneration.

Many European firms, for instance, tie a portion of CEO compensation to ESG-linked KPIs. In India, while some leading companies – especially in IT, financial services, and large conglomerates – are moving in this direction, for most companies, ESG still remains compliance-driven.

One of the challenges is that ESG expertise at the board level is still limited. Most Indian boards lack members with deep sustainability or climate knowledge, which limits the quality of discussion. ESG committees are being set up, but they often operate as compliance-monitoring bodies rather than as drivers of transformation. Too often, the responsibility is pushed down to sustainability teams instead of being embedded into core strategy.

That said, change is visible. Larger firms are now linking ESG to capital allocation, reviewing supply chain risks and exploring new opportunities such as green hydrogen, carbon markets and circular economy models. Investors, both Indian and international, are pushing harder for meaningful oversight, and SEBI’s recent requirement for companies to disclose ESG risks and opportunities at the board level will accelerate this trend.

Over the next five years, boards are likely to become more ESG-literate, bring in directors with relevant expertise, and shift ESG from compliance to long-term value creation. The change may be gradual, but with investor and regulatory pressure rising, it is becoming unavoidable.

NM: Governance, particularly in terms of board diversity, ethics and transparency, remains a challenge. Where do you see the most urgent gaps to be addressed?

MR: Despite notable regulatory advances, key governance gaps remain in the Indian ESG landscape. The most visible gap is board diversity. SEBI requires at least one woman director on listed company boards, but women still make up only about 18 percent of directors in India, compared to over 30 percent in many developed markets. Diversity is not just about representation – it shapes decision-making, innovation and risk management.

Another concern is ethics and transparency. Related-party transactions, beneficial ownership structures and whistleblower protections are often inadequately disclosed. In several corporate governance crises in India, lack of transparency and weak enforcement of ethical codes have been central issues. Independent directors, who are meant to play a critical oversight role, often lack independence in practice.

We also see gaps in how boards oversee emerging governance risks. Data privacy, cybersecurity, supply chain human rights and AI ethics are not yet mainstreamed in governance discussions. Global investors now expect clear oversight on these fronts, and Indian companies risk being left behind if they don’t act.

Closing these gaps will need three big shifts: tighter regulation and enforcement, stronger board capacity with directors with ESG and sustainability expertise and a culture of ethics that goes beyond compliance to genuine transparency. Without strong governance, progress on the environmental and social pillars will not be seen as credible.

NM: What are some best practices India can borrow from the outside world to strengthen corporate ESG governance?

MR: There are several global practices India can adapt to strengthen ESG governance. From the EU, the idea of double materiality is especially useful. It requires companies to consider not just how sustainability issues affect them, but also how their operations affect the environment and society. This makes ESG shift from being inward-looking to stakeholder-focused.

From the US, shareholder engagement offers lessons. Mechanisms like “say-on-climate” votes, where shareholders approve corporate climate plans, create accountability at the highest level. India’s investor community could play a bigger role in pushing boards to treat ESG seriously.

Japan brings another valuable approach: stewardship codes and a long-term outlook. Japanese companies often focus on creating value that lasts decades, aligning corporate behaviour with the interests of both investors and society. Such an approach can help Indian firms balance growth with resilience.

India should also adopt global best practices in specific areas, such as climate risk stress testing widely used in the UK, biodiversity reporting as seen in the TNFD in Europe and linking executive pay to ESG performance, a standard practice among many global firms. Another lesson is the use of independent assurance to validate ESG data – this significantly boosts investor confidence. Ultimately, India needs to borrow global best practices but tailor them to Indian realities.

NM: India has set an ambitious 2070 net-zero target. Do you think the pathway is realistic, given the country’s growth needs and the challenges of addressing the hard-to-abate sectors?

MR: India’s 2070 net-zero target is both ambitious and practical. It is ambitious because cutting emissions to zero in a country of 1.4 billion people with fast-growing energy needs is an enormous task. It is practical because the timeline recognises India’s development realities and the need to lift millions out of poverty while still decarbonising. Unlike developed countries aiming for 2050, India needs more time to balance growth with climate action.

The pathway is realistic if three conditions are met. First, renewables must scale up rapidly. India has already become a leader in solar, and hitting the 500 GW target by 2030 will be a turning point. Second, hard-to-abate sectors like steel, cement and heavy transport need breakthroughs such as green hydrogen, carbon capture and electrification. Third, the financing gap has to be closed. Estimates suggest over $10 trillion will be needed for this transition, which means both global climate finance and domestic green investment must grow.

The challenge is not technical potential as India has abundant renewables and innovation capacity. The challenge is execution: consistent policies, strong state-level capacity, and managing the social impact of moving away from coal. Supporting workers and communities through a just transition will be critical for stability.

In sum, India’s target is achievable if this decade delivers strong action. The 2020s must be the decade of acceleration in renewables, efficiency, and green finance. Otherwise, the pathway will become steeper in later decades.

NM: How do you view India’s role in emerging carbon markets and the potential to leverage renewables and efficiency gains to bridge the gap?

MR: India is well placed to play a major role in carbon markets. It already has one of the world’s largest renewable energy programmes and a strong record of energy efficiency through initiatives like Perform, Achieve and Trade. These create a solid base for generating credible, verifiable carbon credits. The government’s launch of the Carbon Credit Trading Scheme is a crucial step, but for India to benefit fully and for the credits to be trusted globally, it must focus on robust monitoring, reporting and verification systems.

At the same time, renewables and efficiency gains can reduce emissions domestically, while also freeing up “carbon space” for hard-to-abate sectors such as steel, cement, and aviation, where the transition will take longer. By positioning carbon markets as both a climate solution and a development tool, India can attract international finance while creating co-benefits for local communities. For example, afforestation projects linked to carbon credits could generate rural jobs, while clean cooking and waste management projects could improve health outcomes.

If India manages to link its carbon market with global ones while ensuring environmental integrity, it could become a hub for high-quality credits.

NM: ESG is often dominated by the “E.” How can Indian companies bring the social dimension, such as human rights, labor practices, mental health and well-being, into sharper focus?

MR: Indian companies can and must bring much greater depth and visibility to the “social” pillar of ESG by moving beyond compliance and actively integrating human rights, labor practices, and employee well-being into their core strategies. Global investors are also paying closer attention to social indicators, whether on supply chain labour practices, community relations, or workplace diversity.

Board-level leadership is central to this shift. Social KPIs must be tied directly to executive accountability, linking social impact metrics such as workforce diversity, equitable pay, or supplier labor standards to performance reviews.

Supply chain audits, particularly in sectors like textiles, agriculture, and construction, should become the norm to identify and address risks of forced labour, unsafe conditions, and wage exploitation. To raise the profile of the social dimension, companies need to set clear, measurable goals related to workplace safety, fair wages, gender and diversity, and labor rights throughout their value chain, not just within direct operations.

Equally important is employee well-being, especially mental health—a subject that remains under-discussed in many Indian workplaces. Providing counselling services, flexible work arrangements, and safe grievance mechanisms can improve productivity, retention, and overall workplace culture.

Ultimately, embedding the “S” requires leadership from the top. Boards must treat social risks as business risks, and companies must be prepared to disclose progress publicly. Doing so will make them more attractive to global investors who increasingly favour companies that balance profitability with purpose.

NM: What does a “just transition” look like in India, given the reliance on coal and traditional industries for employment?

A just transition in India is about moving to a low-carbon economy in a way that does not leave workers and communities behind. Coal is central to India’s energy system, and millions of people depend on coal mining, coal power and linked industries for their income. Shutting these sectors too quickly, without providing alternatives, could lead to social unrest and economic hardship.

For India, the transition must be gradual and carefully planned. This involves reskilling workers for jobs in clean energy, energy efficiency, and emerging sectors such as green hydrogen and electric mobility. It also means creating new economic opportunities in coal-dependent regions, whether through renewable energy projects, agro-based industries, or services. At the same time, social protection, such as pensions, healthcare, and income support, will also be important for workers who cannot be immediately absorbed into new jobs.

India can also learn from international experiences but must tailor them to local realities. For instance, coal regions could be designated as “just transition zones,” with targeted public and private investment to diversify their economies. Most importantly, communities must be involved in the planning, so that they are partners in change rather than passive recipients.

NM: ESG capital is flowing faster globally than in India. What barriers do you see for Indian companies in accessing sustainability-linked finance?

MR: India has a big opportunity to attract ESG-linked capital, but several barriers hold companies back. The biggest is credibility. Many global investors find Indian ESG disclosures inconsistent and hard to compare across companies. Without standardised, assured data, it is difficult for investors to assess risk. This reduces the flow of capital into Indian markets.

Another barrier is scale. Global green bonds and ESG funds usually target large issuances, making it harder for smaller companies or MSMEs to participate. In India, where MSMEs form the backbone of the economy, this creates a structural disadvantage. There is also a lack of clarity on sustainable finance taxonomies – definitions of what counts as “green” or “sustainable” vary which creates confusion for both issuers and investors.

Finally, macroeconomic factors also play a role. High capital costs in India and currency risks often make global sustainability-linked finance less appealing. Without better ways to manage these risks, Indian companies may be reluctant to seek funding from global sources.

Addressing these barriers will require three things: stronger ESG reporting and assurance, development of domestic green finance markets, including mechanisms tailored for MSMEs and clear regulatory frameworks that align with global standards.

NM: Looking ahead five years, do you believe India can position itself as a global leader in sustainability? What must change to get there?

MR: India is already seen as a key player in global sustainability, but whether it becomes a leader will depend on the choices made in the next five years. On the positive side, India is the world’s lowest-cost producer of solar energy, has one of the largest renewable energy pipelines, and is actively pursuing green hydrogen, EVs, and large-scale afforestation. Its startup ecosystem is also generating climate-tech innovations that can scale quickly.

However, leadership is not only about ambition – it is about credibility and delivery. To be seen as a leader, India must strengthen three areas. First, governance and enforcement. Without credible ESG disclosures and strong corporate governance, global investors will remain cautious. Second, finance. India will need to mobilise far greater green finance flows, both domestically and internationally, and build institutions that can channel funds effectively. Third, state-level implementation. Energy, urban planning, and transport are state subjects, and much of India’s climate progress will depend on whether states have the capacity and incentives to deliver.

By taking these steps, India can position itself as a model for inclusive, low-carbon development, and the next five years will be critical in setting this trajectory.

Nirmal Menon

Related posts

Subscribe

Error: Contact form not found.